A new study of mine has just been published in the Journal of Anatomy! The paper is open access, courtesy of UC Davis, so it is free to access and read for all. You can find it here.

The paper is part of a special issue on palaeohistology guest edited by my friend Mateusz Wosik and yours truly. We had a huge amount of interest in the topic, so what started out as a single issue aiming for ~10 papers ended up becoming a whopping double-issue with 26 papers, spanning virtually the entire range of vertebrates! The physical volume should be released sometime in the fall, but nearly all the articles are already available online (I think mine might have been the last to be released). You can read more about the inspiration for the special issue, and what it contains, here.

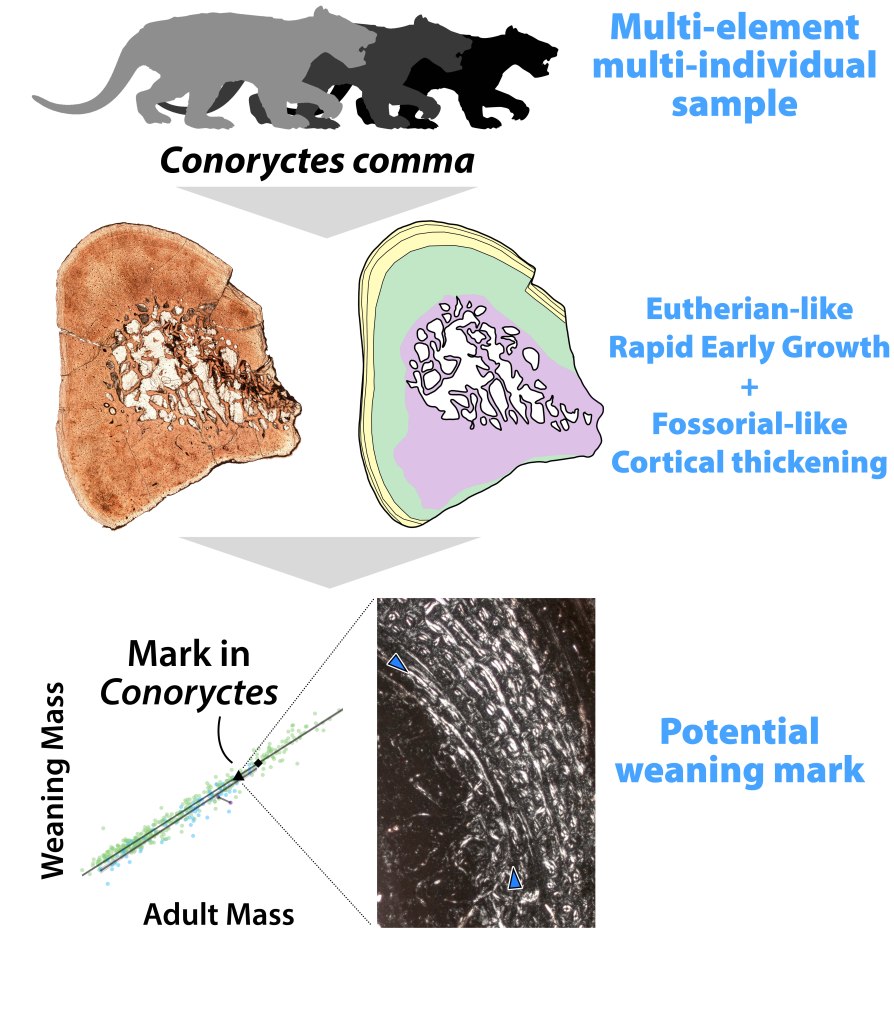

My paper in the issue is the second of a series of detailed papers I’ve envisioned about the life histories of Palaeocene mammals (those living just after the dinosaur extinction). The first, on Pantolambda, used some new techniques to estimate different aspects of reproduction in this animal with unprecedented precision. This new paper follows up on a different species, but a close neighbour of Pantolambda on the tree of life: Conoryctes.

Conoryctes, meaning “digger with conical teeth”, would have looked sort of like a small-sized blend between a bear, a pig, and a hyena. It had a stocky build, like many mammals of its time, and it probably spent a good deal of its time digging (something our study supports). What makes Conoryctes most interesting to me, however, is that it belongs to a special lineage, one that has fossil representatives both before and after the Cretaceous extinction. This is very important, because although we know that mammals crossed this boundary, the relationships between the small precursors living alongside the dinosaurs and the larger species that inherited the Earth have remained mostly unclear. And what’s even more special is that it’s likely that Conoryctes and its kin, called Taeniodonts (‘ribbon teeth’), were just outside of the group we call placental mammals.

Learn more about how scientists group species

When scientists ally species into broader groups, they do so with the aim of making ‘natural’ groups. A ‘natural’ group consists of all the species that share a single common ancestor (which is usually hypothetical, not an actual fossil). The idea is that we can trace the genealogy of all the species in a group back to a single point, the same way you could trace back your family members to your great-great-grandmother. Conoryctes is akin to our great-great-grandmother’s sister: we’re not her direct descendants, and she’s sort of closely related to us, but it’s in a different branch of the family tree. In this case, that branch ultimately went extinct and no descendants are alive today. But, Conoryctes‘ family and our great-great-grandmother share a common ancestor, too, and this means that Conoryctes holds important information about what traits our great-great-grandmother could have inherited from her parents (especially, as in this case, if we’ve lost all information about our great-great-grandmother). So, if we’re interested in why our great-great-grandmother was so successful when her siblings weren’t, it’s really important to study her siblings.

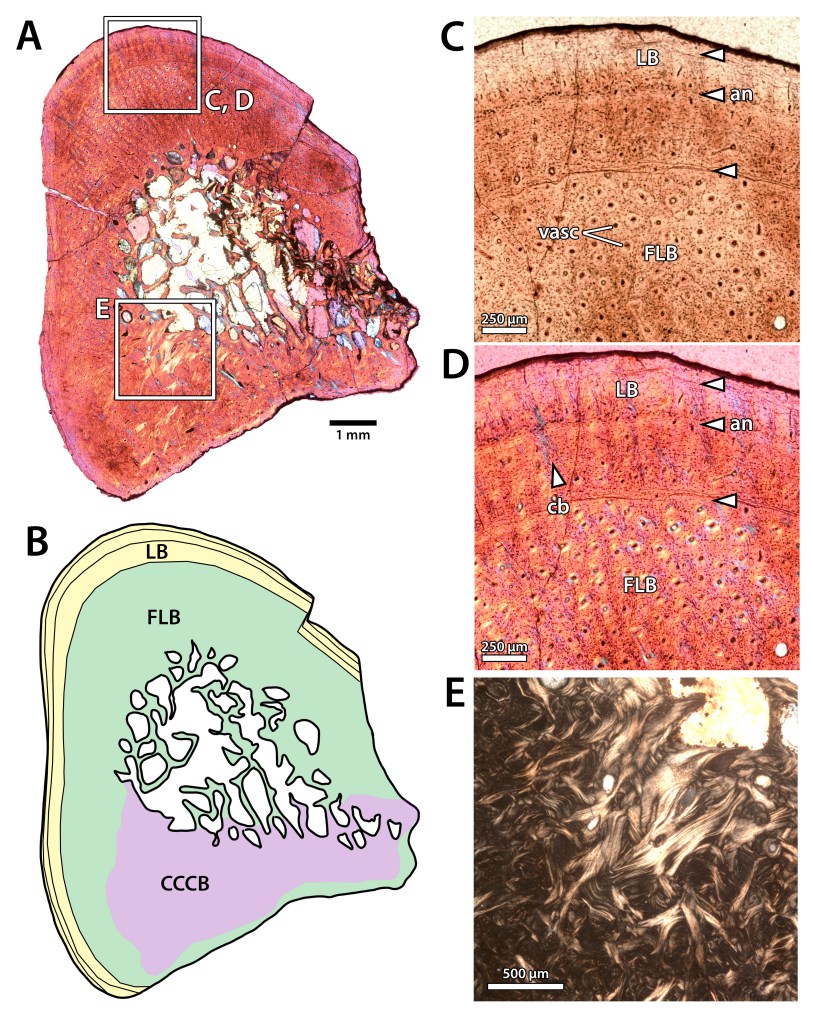

With that context, what we found in Conoryctes is quite interesting. We made thin-sections of the limb bones to look at the rate they grew, as well as yearly growth marks that tell us the age of the individuals (like tree rings). In Conoryctes, these signals looked just like what we see in placental mammals — that means our placental common ancestor (our ‘great-great-grandmother’) probably inherited fast growth from its ancestors. The positions of the yearly growth marks tell us that Conoryctes grew close to adult size (~14 kg) in its first year, similar to many similar-sized placental mammals today. The bones also give us another interesting clue about Conoryctes’ life: a sort of smeared growth mark that probably reflects the struggle of weaning in early life (we found a similar mark in Pantolambda). These results are so far the strongest evidence that the distinctive life history of placental mammals evolved before the Cretaceous extinction, and so might have factored in their meteoric rise afterwards (although they weren’t alone in this attribute).

Another interesting thing came up in our thin sections. In cross section, most limb bones are sort of like a donut, with an internal space (for marrow) surrounded by a ring of bone. In Conoryctes, the donut hole was small and filled up with a complex tissue formed by multiple layers of successive deposition. This seems to be a common trait in species that dig, potentially as an adaptation for dealing with the stress and strain that digging puts on the forelimbs. So we can say that both the outside and the insides of the bones in Conoryctes support the hypothesis that they were digging a lot of the time — either for food, or for burrows, or both. Altogether, the data from inside the bones help to flesh out our picture of the life and times of Conoryctes.

This paper is my second paper focusing on mammal growth, in hopefully a very long line of studies. I already have some other projects lined up, awaiting the last final bits of data before I can get down to writing up the findings. Studies like this one will be a major part of my work going forward, and the emphasis of my new lab at Stony Brook. So if you find this kind of research interesting, be sure to stay tuned for more or get connected!