It feels like I just got to Davis, and I’ve enjoyed my time in California, but I’m off to the next place already! I am thrilled to announce that I will be joining Stony Brook University’s Department of Anatomical Sciences in a tenure-track role this Fall!

It’s surreal to think that I’ve finally found a permanent home for my research, after what feels like a long journey. I’m fortunate to have been able to undertake this journey–there are many talented people who never get the opportunity–and I have benefitted tremendously from a TON of support: my family for encouraging me in the first place; my friends and colleagues for companionship and mentorship; but most importantly, my wife, Brittany, who has been steadfast at my side through all of these adventures.

So what will the Funston Lab look like at Stony Brook? Here’s my vision on short-, medium-, and long-terms.

First steps:

In the next year, my main goal will be to build my lab space. This means buying equipment, calibrating tools and techniques, setting up a field program, and scrambling when I realize I’ve forgotten to account for some core item. The Department and the Dean’s office have agreed to a very generous support package that means I get to build my dream setup.

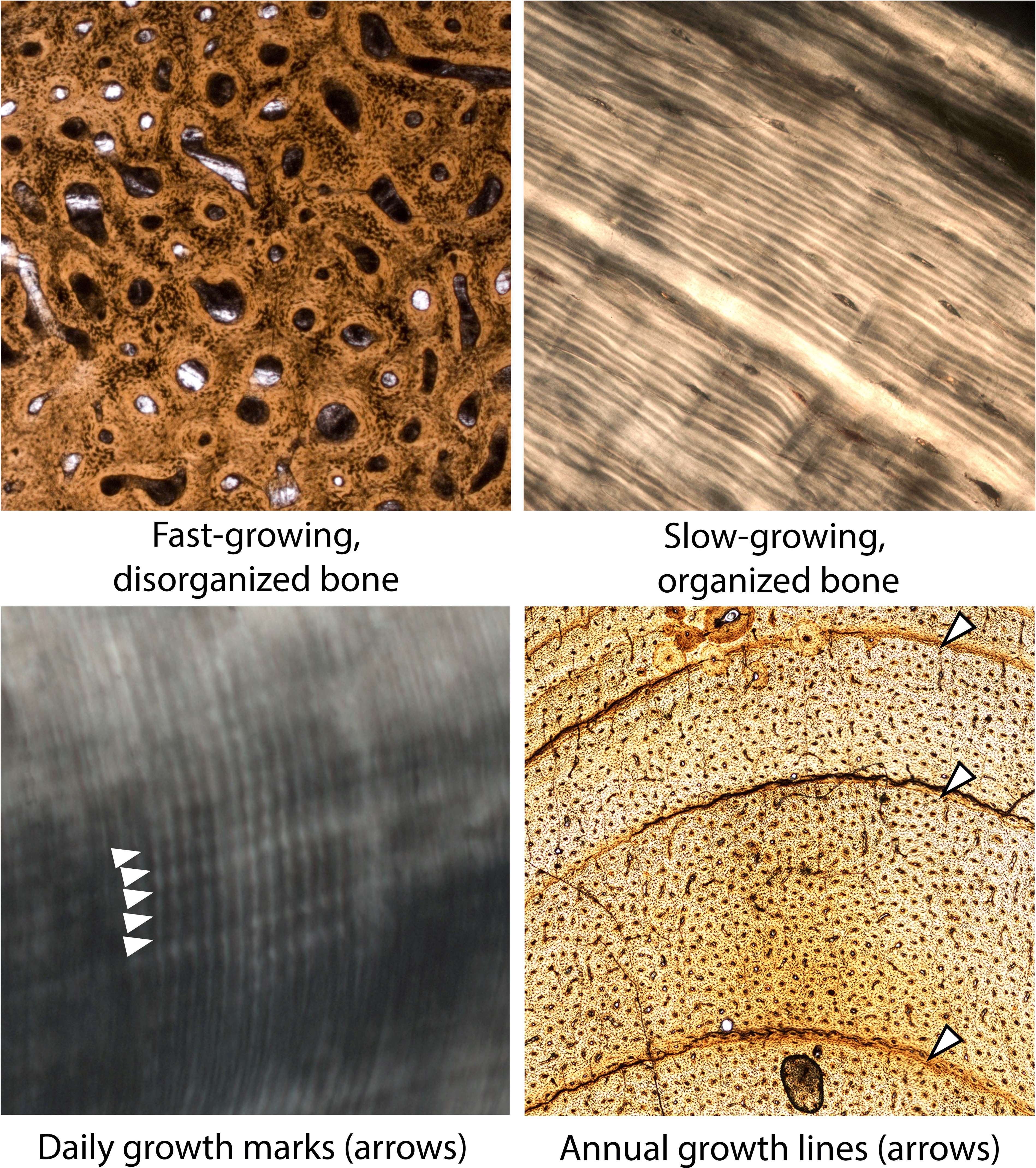

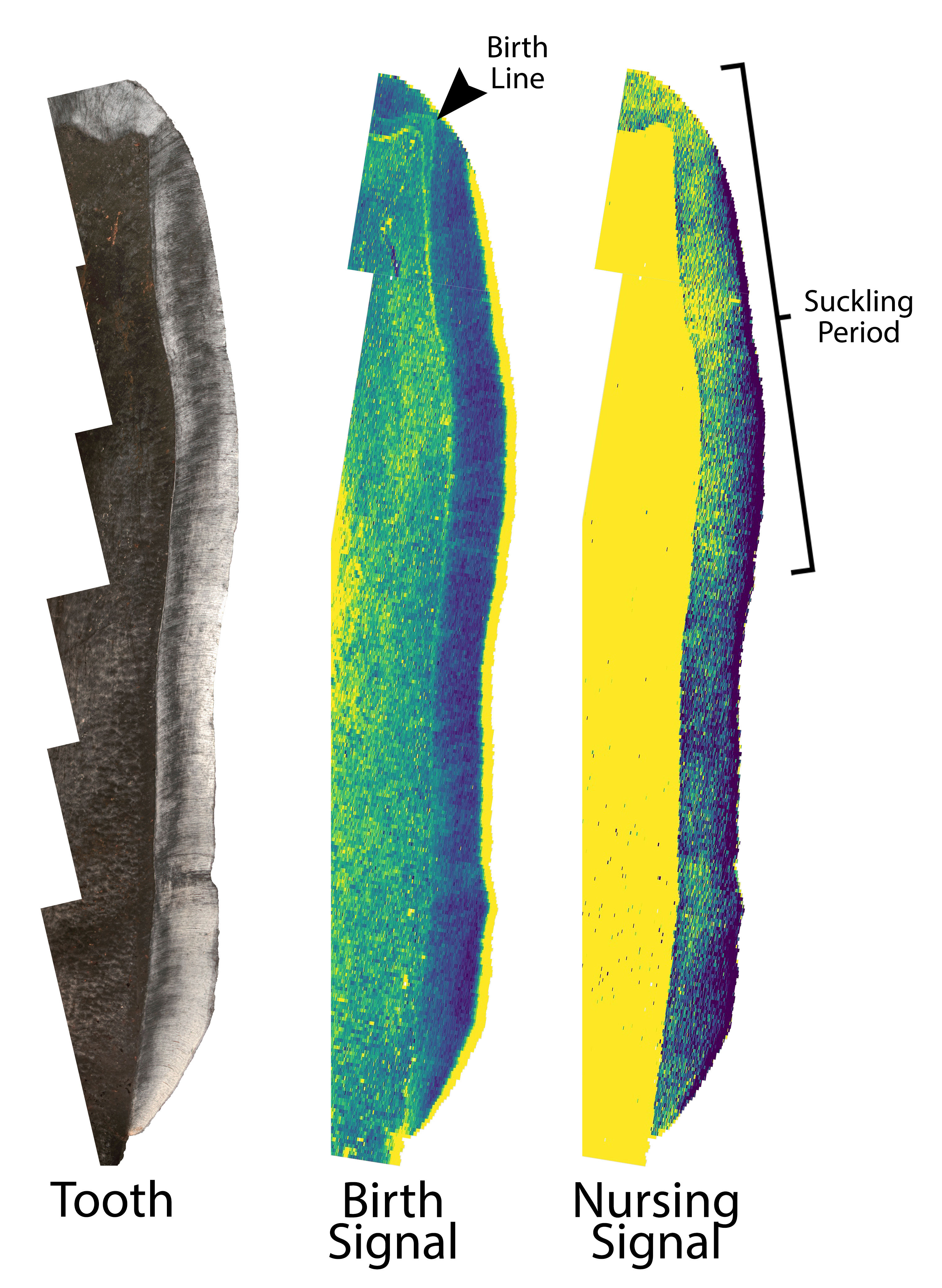

The main focus of my research and my lab will be palaeohistology, the study of fossilized tissues on a microscopic level. My lab space will have the ideal pipeline for making the thin sections that underlie my work, ranging from tiny teeth to chunky bones. The first step is preserving the anatomical data of the specimens, which means 3D modelling and photography. I’ll have a dedicated specimen photography/photogrammetry setup (taking advantage of my experience with cameras), and in the future I might look into acquiring a µCT scanner for microscopic x-ray analysis of specimens. Fortunately, the Brookhaven Synchrotron is just next door, so I’ll also be able to take advantage of that to scan specimens at super-high resolution in the meantime.

Then the fun part begins: thin sectioning. This means a vacuum chamber for embedding in epoxy, a slow-spinning saw for precision cutting, and polishing equipment for grinding slides to the right thickness. Just like the setup I was trained on at UAlberta, and the one I built at the University of Edinburgh. Once the specimen is translucent, it needs to go under a microscope for imaging — I’ll have an automated imaging system inspired by the one at the Royal Ontario Museum. All my training is coming together! I’ll also be focusing a lot on analyzing the chemistry of the thin sections, and I’m excited that the Department of Earth Sciences next door has a perfect setup for that kind of work. Finally, we’ll need computers to store the data and software to analyze the results.

Next steps:

So what data will I be collecting, and why? My research will focus on big questions in mammal evolution: how did mothers’ care of their young change through time, and what impact did this have on their evolutionary patterns? I will be building on the techniques and approaches from my past research, mapping daily growth marks in the teeth and measuring chemical concentrations that represent changes in diet, from birth, to suckling, to independence. This gives us a daily timeline of pregnancy and breastfeeding in ancient mammals–letting us use statistics to test our hypotheses.

I can’t be a one-man army, so once my lab is set up, I’ll be looking to grow. Starting from my second year, I’ll be actively recruiting students and postdocs. My lab will remain small but mighty: 1-2 students max, 1-2 postdocs max, and a handful of undergraduates, working at the very cutting edge (pun intended) of mammalian evolution. If you might be interested in joining the team from 2027 onwards, get in touch.

There are a few main projects we’ll focus on for the first five years: 1) clarifying the divergence of marsupial and placental strategies; 2) testing if reproductive strategies affect extinctions; 3) marsupial dental development and milk; 4) post-dinosaur mammal communities; and 5) exploration of pregnancy and suckling in certain lineages throughout mammal history. Whereas the first four of those topics will probably bear fruit within five years, in the form of scientific publications, the last is exploratory, part of my long-term research vision, and the excitement is that we don’t know what we’ll find.

Future:

That long-term goal for my research programme is to understand the links between life history (the pattern and pace of life stages) and evolution, not just in mammals, but across animals with bones and teeth. Mammals are a perfect model to start with, because they have some peculiarities that lead to better preservation of the right signals, but I’d like to generalize rules and test them in other groups, too. Of course, I can’t just give up researching dinosaurs!

It took a while for me to find the uniting theme that connects all of my interests, but I always came back to the natural world around us today. I’m interested in fossils because they tell the story of how the world came to be, and they can reveal the long-term rules that govern evolution. What I’d ultimately like to do with my research is to understand how life history is linked to extinction and diversification on long time scales, so that we can use those lessons to better protect the world around us today. This isn’t a new idea by any means: conservation palaeobiology is a burgeoning field, and it will take a lot of work to bridge the gaps and make my fossil research relevant. But I’m excited to find my place in it, and to be starting that journey at Stony Brook.

Congrats Greg! Looks like a gre

LikeLike